https://www.artnome.com/news/2018/8/8/why-love-generative-art

Why Love Generative Art? — Artnome

Over the last 50 years, our world has turned digital at breakneck speed. No art form has captured this transitional time period - our time period - better than generative art. Generative art takes full advantage of everything that computing has to offer, p

www.artnome.com

Why Love Generative Art?

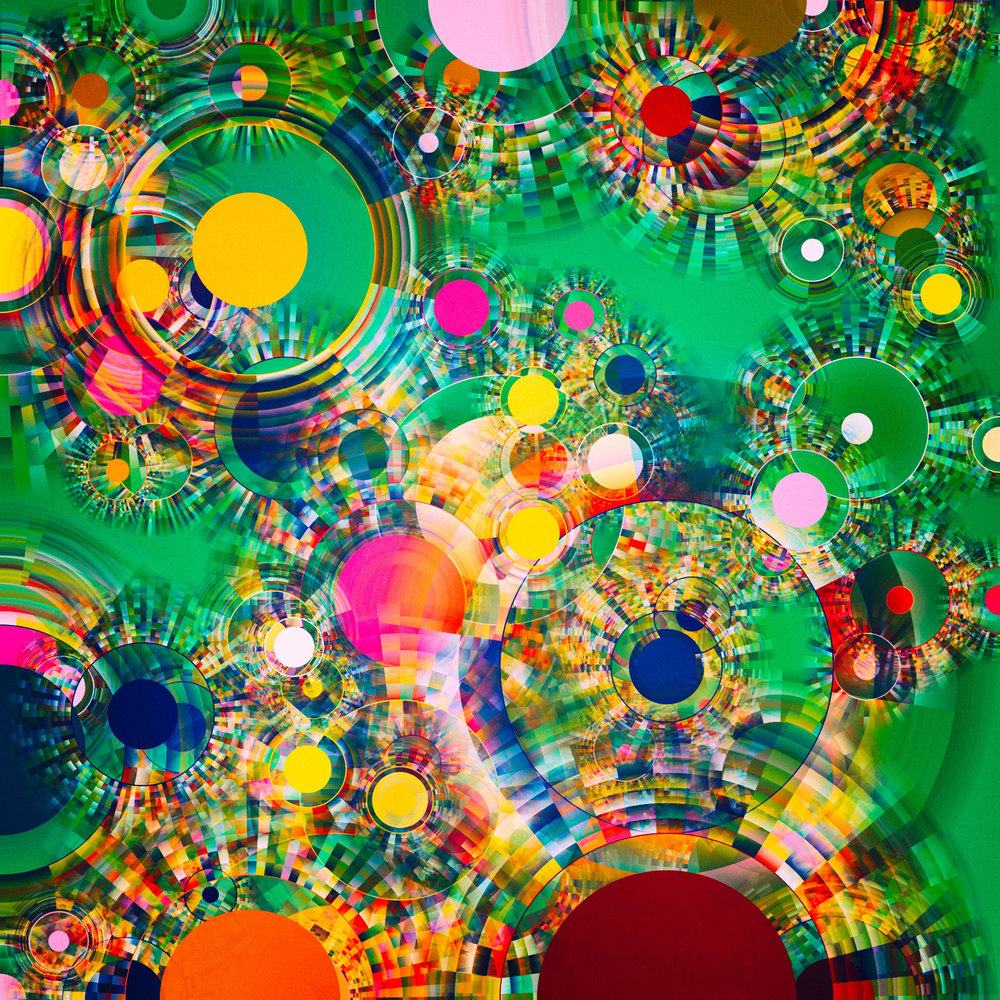

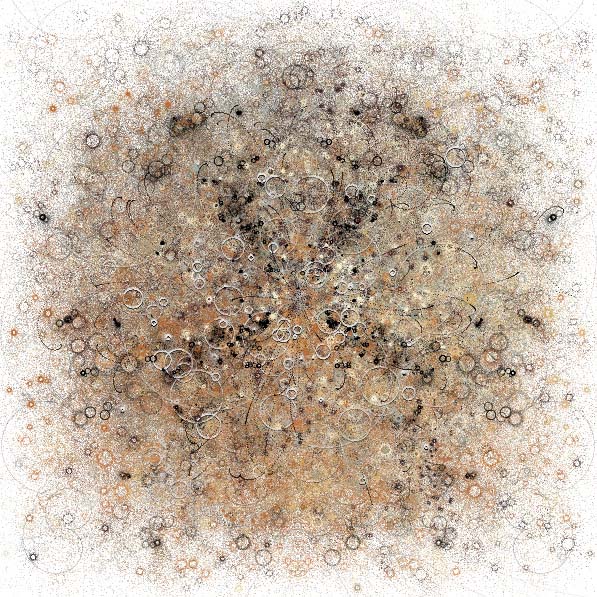

VVRRR - Manolo April, 2018

Over the last 50 years, our world has turned digital at breakneck speed. No art form has captured this transitional time period - our time period - better than generative art. Generative art takes full advantage of everything that computing has to offer, producing elegant and compelling artworks that extend the same principles and goals artists have pursued from the inception of modern art.

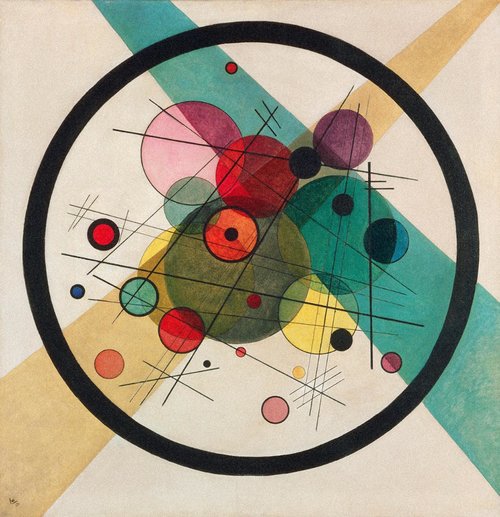

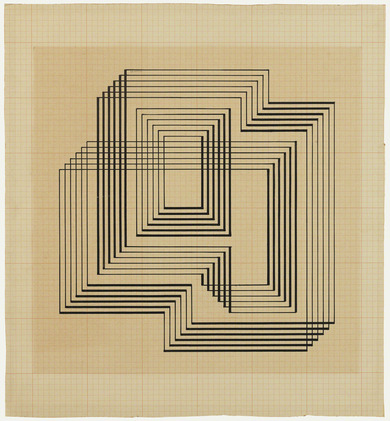

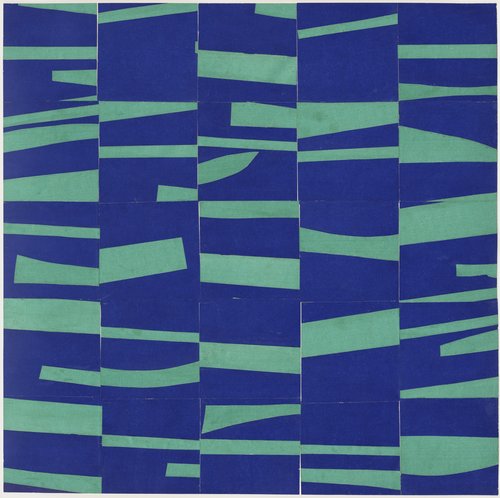

Geometry, abstraction, and chance are important themes not just for generative art, but for all art of 20th Century. As an art historian and an amateur generative artist, I see a clear line of influence on generative art starting from Cézanne and shooting straight through to the:

- Fracturing of geometry in Analytical Cubism

- Emphasis on technology, machine aesthetic, and mechanized production from Futurism, Constructivism, and the Bauhaus

- Introduction of autonomy and chance in Dada, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism

- Anti-figurative aesthetic, bold geometry, and intense color of Neoplasticism, Suprematism, Hard-edged Abstraction, and OpArt

- Use of algorithms by Sol Lewitt and others

Group IV, No. 3. The Ten Largest, Youth - Hilma af Klint, 1907

Suprematist Composition - Kasimir Malevich, 1916

Circles in a Circle - Wassily Kandinsky, 1923

Highway and Byways - Paul Klee, 1928

Rotorelief 1 (Optical Disks) - Marcel Duchamp, 1935

Concentric Squares - Josef Albers, 1941

Study for Meschers - Ellsworth Kelley, 1951

Red Meander - Annie Albers, 1954

Burn - Bridget Riley, 1964

Wall Drawing 11 - Sol Lewitt, 1969

To my eyes, all of these influences and more are tied directly into early generative art through to its modern day practitioners. So I cringe when I hear the majority of my art-loving friends dismiss generative art as being irrelevant, not of interest to them, or even unworthy of being called art.

Every generation claims art is dead, questioning why it has no Michelangelos, no Picassos, only to have their grandchildren point out generations later that the geniuses were among us the whole time. We have a unique opportunity to embrace some of the most important artists of our generation while most of them are still living (and working). I hope to do my part in facilitating this through this article. Here we will explore why people so often struggle with generative art and:

- Offer a simplified definition of generative art

- Abolish ideas that credit machines for making generative art and not the artists themselves

- Give some non-technical examples of how generative art works

- Explore some of the history of generative art going back to the early 1960s

- Highlight my favorite generative artists and share some of their work

- Examine the world of generative AI art that is just now starting to get mainstream attention

Hopefully by the end of this post you will either share my love for generative art or you will at least be able to intelligently communicate your distaste for the genre.

What is Generative Art?

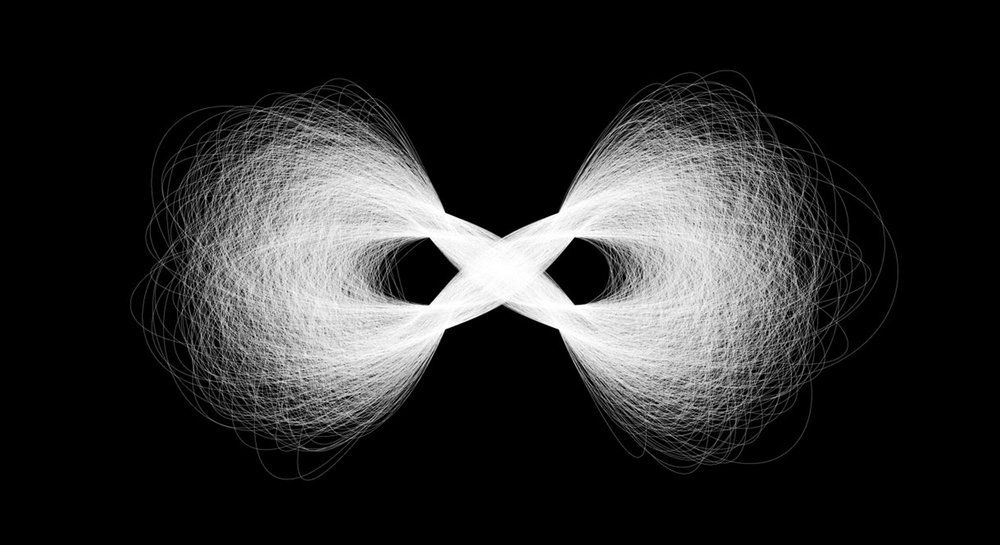

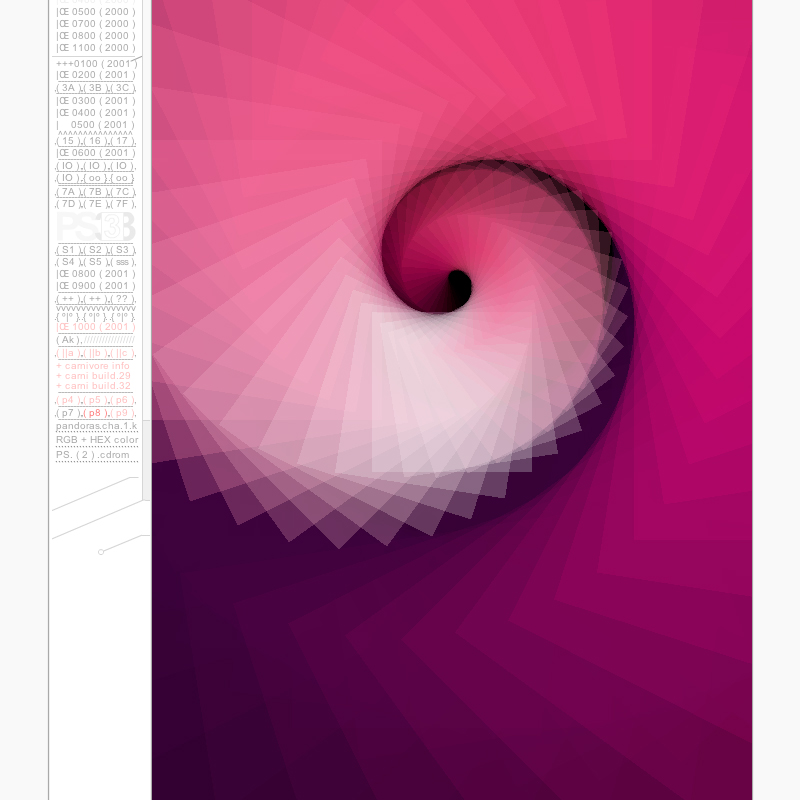

Path - Casey Reas, 2001

One overly simple but useful definition is that generative art is art programmed using a computer that intentionally introduces randomness as part of its creation process. This often brings up two common but misguided viewpoints that hold people back from appreciating the beauty and nuance of generative art.

Myth One: The artist has complete control and the code is always executed exactly as written. Therefore, generative art lacks the elements of chance, accident, discovery, and spontaneity that often makes art great, if not at least human and approachable.

Myth Two: The artist has zero control and the autonomous machine is randomly generating the designs. The computer is making the art and the human deserves no credit, as it is not really art.

The truth is that generative artists skillfully control both the magnitude and the locations of randomness introduced into the artwork.

Controlled randomness may sound contradictory, but if you are an artist or an art historian, you know that artists have always sought ways to introduce randomness into their work to stimulate their creativity. Thinking about the process of coding generative art as being similar to painting or sketching is actually spot on. In fact, we will see that the tool favored by most generative artists refers to the individual artworks produced as "sketches.”

Let's Look at Some Early Examples of Generative Art

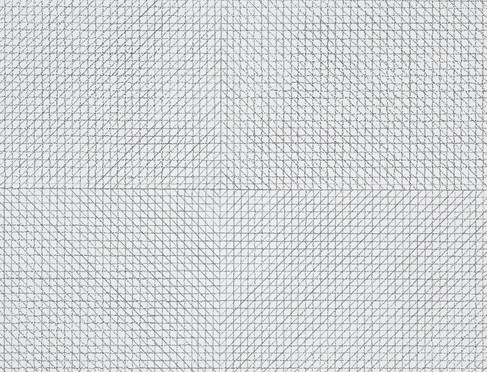

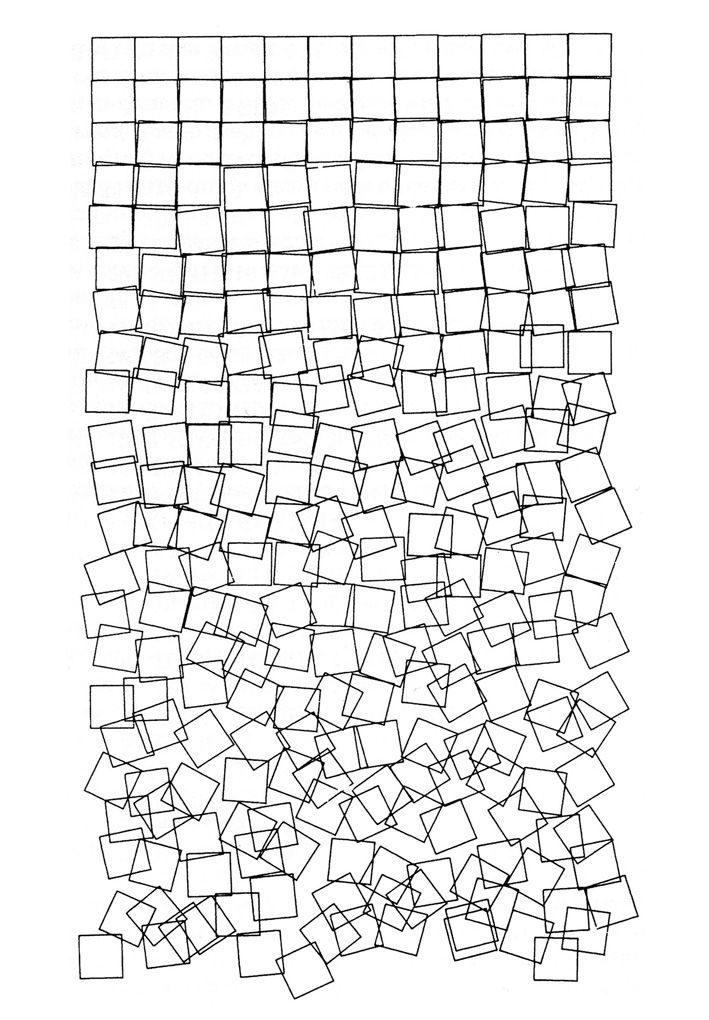

Let’s look at Georg Nees' 1968 work Schotter (Gravel), one of the earliest and best-known pieces of generative art. Schotter starts with a standard row of 12 squares and gradually increases the magnitude of randomness in the rotation and location of the squares as you move down the rows.

Schotter (Gravel) - Georg Nees ,1968

Imagine for a second that you drew the image above yourself using a pen and a piece of paper and it took you one hour to produce. It would then take you ten hours if you wanted to add ten times the number of squares, right? A very cool and important characteristic of generative art is that Georg Nees could have added thousands more boxes, and it would only require a few small changes to the code.

Unlike analog art, where complexity and scale require exponentially more effort and time, computers excel at repeating processes near endlessly without exhaustion. As we will see, the ease with which computers can generate complex images contributes greatly to the aesthetic of generative art.

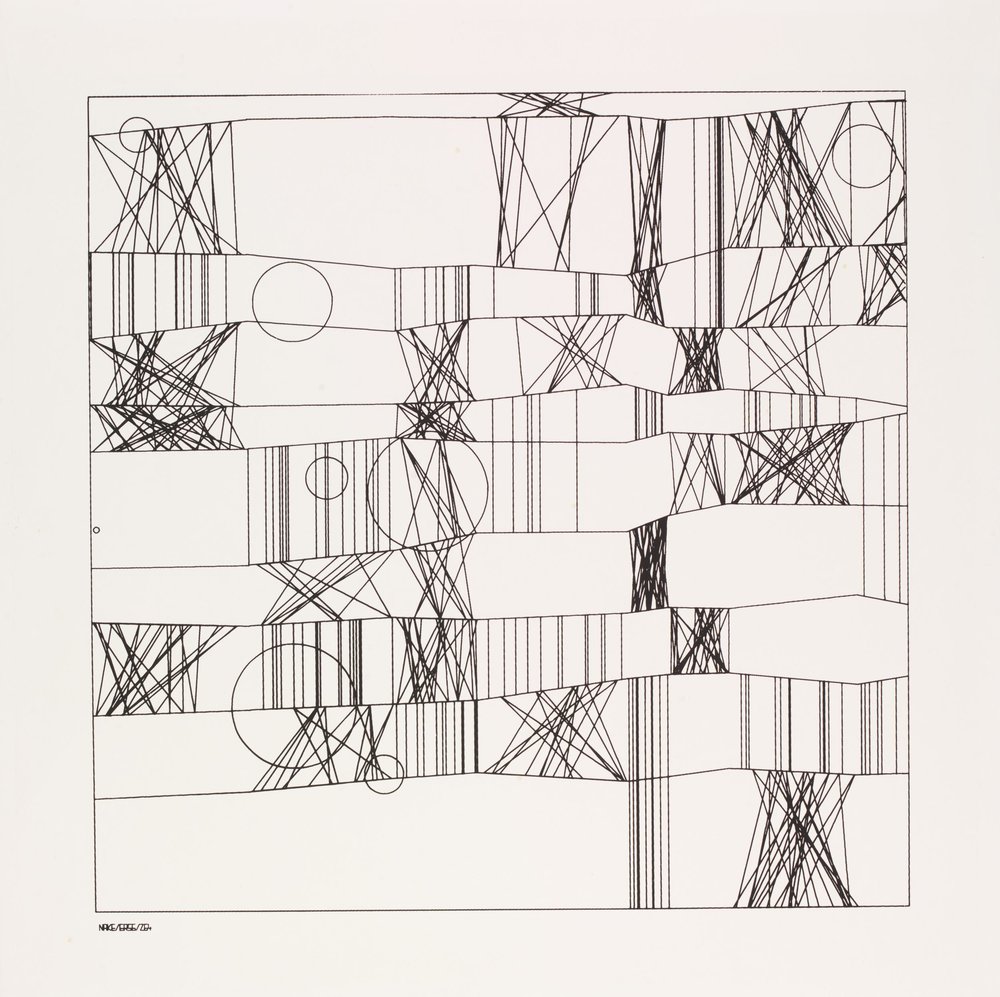

As with many innovations, there were several pioneers exploring the potential for generative art in its first few years. Frieder Nake and Michael Noll, along with Georg Nees, were all exploring the use of computers to generate art. Back then, computers typically had no monitors, and the work was shared by printing the art on plotters, large printers designed for vector graphics.

Hommage à Paul Klee - Frieder Nake, 1965

Pioneering Women of Generative Art

It was hard for anyone to be a generative artist in the ‘60s and ‘70s. Computers were primitive, filled entire rooms, and access to them was extremely limited. Today most people grew up with computers in their homes and now carry them in their pockets. The majority of people in those early decades of computing had little to no contact with computers or frame of reference outside of science fiction. Against this backdrop and in a time where women faced tremendous sexism in the workplace, a large number of female generative artists emerged, making key contributions to the craft and the community.

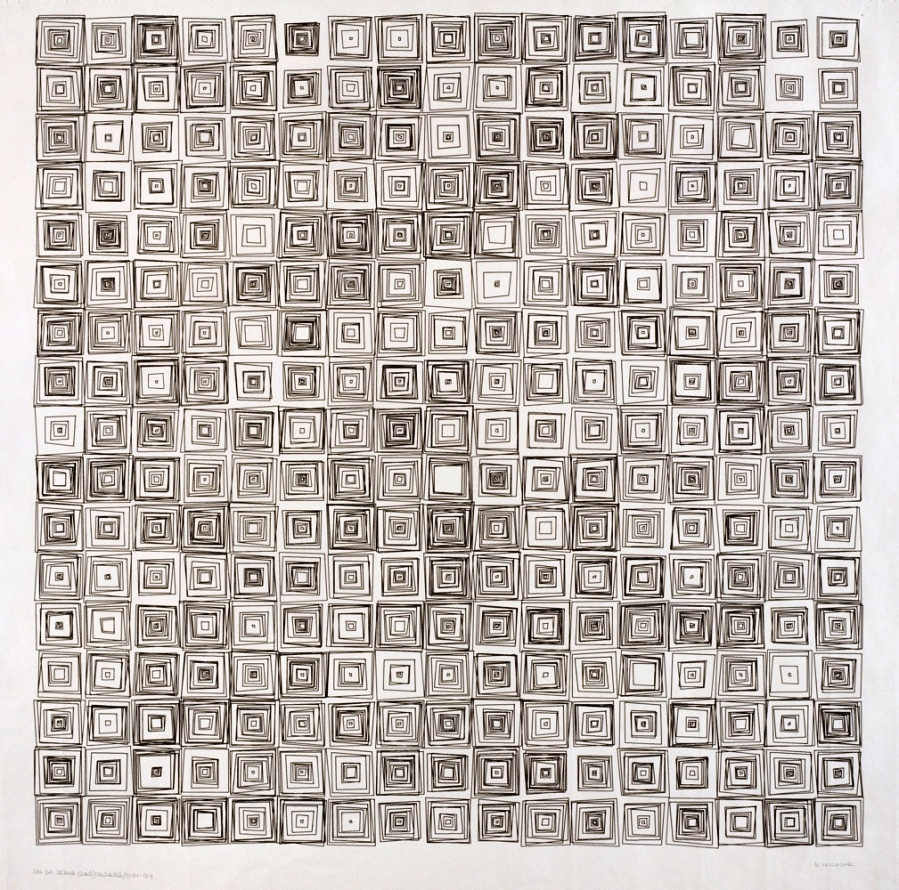

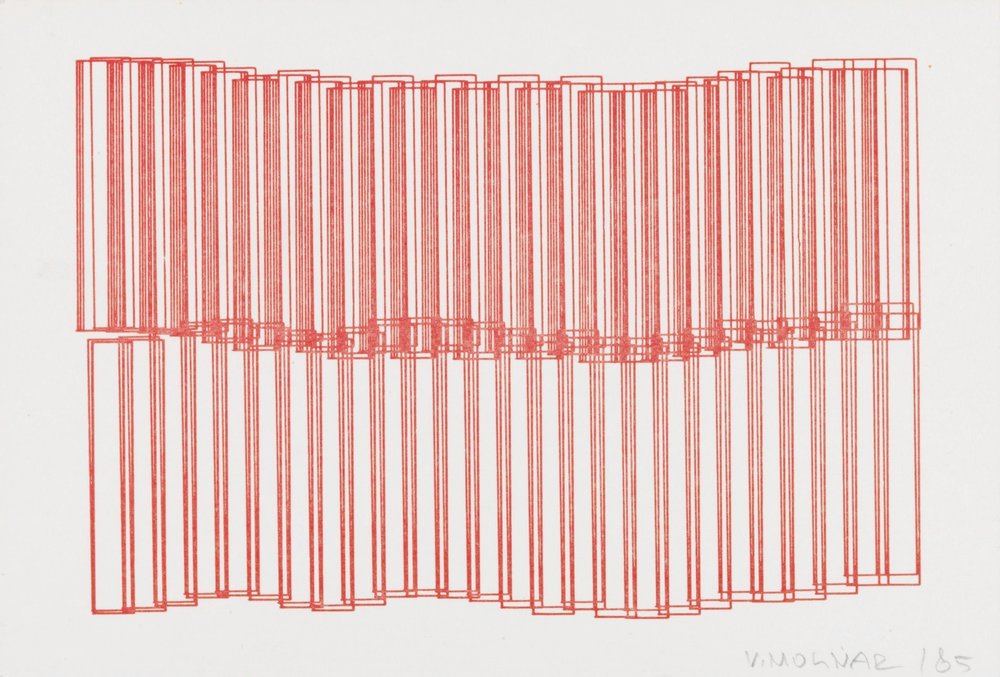

Vera Molnár is one of the more prolific generative artists (a personal favorite of mine), and her work spans several decades. Below we see Molnár’s works from the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s.

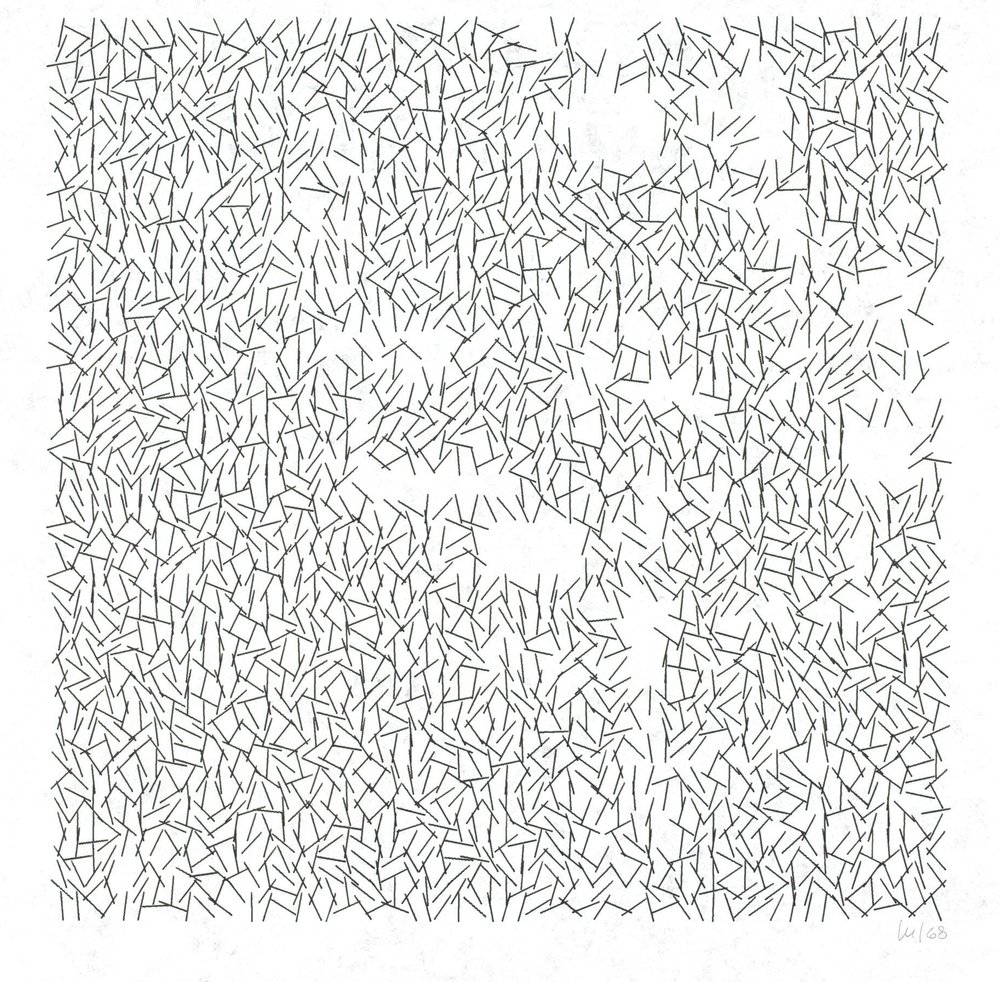

Interruptions - Vera Molnár, 1968/69

(Dés)Ordres - Vera Molnár, 1974

Untitled - Vera Molnár, 1985

Aware of the general perception of computers as cold, logical machines, Molnár spoke of the creative and humanistic gains it presented to her as an artist:

Without the aid of a computer, it would not be possible to materialize quite so faithfully an image that previously existed only in the artist's mind. This may sound paradoxical, but the machine, which is thought to be cold and inhuman, can help to realize what is most subjective, unattainable, and profound in a human being.

Generative artist and art researcher Lillian Schwartz worked as artist-in-residence at Bell Labs starting in 1968 for over 34 years. Her credentials are impressive. She was the first to have generative art acquired by the MoMA and is often credited, along with her collaborator Ken Knowlton, with being the first to exhibit animated digital work as fine art. In a 1982 interview in the Los Angeles Times, Lillian described the cool reception she received from her art world peers when she introduced the computer into her art making practice:

I had a reputation in the arts before I got involved in these areas, but when I started using computers, my fellow artists began to look on me as a prostitute. I haven’t been able to find an artistic circle where I can discuss the aesthetics of my work. I've had to replace my artist friends with computer scientist friends.

Aside from her generative artwork, Lilian is one of my personal heroes for pioneering the use of computer databases in the analysis of art history (my life's passion). She shocked the world in 1984 when she used a computer to prove that Da Vinci himself was in fact the model for the Mona Lisa.

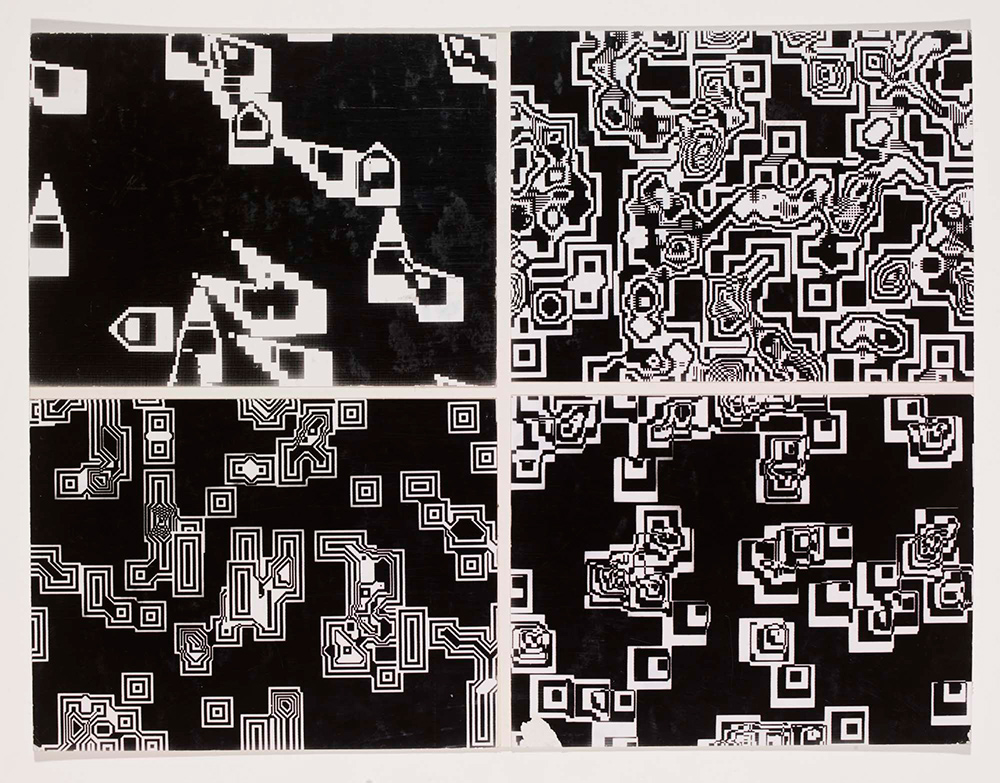

Pixillation, photographic film stills - Lillian Schwartz, 1970

Other key female generative artists from the early days of generative art who made enormous contributions in popularizing the genre include Sonia Landy Sheridan, who founded the first generative systems department at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1970, and Grace Hertlein, who helped to popularize the first annual generative art competition when she became arts editor for Computers and Automation Magazine in 1974.

MIT summer sessions poster - Muriel Cooper, 1958

Though not known to be a programmer, Muriel Cooper had as much influence as anyone in establishing the aesthetics of the computing revolution. Cooper was trained in the design principles of the Bauhaus and influenced by her friend, master designer Paul Rand. Cooper imbued these principles at MIT, where she served as a long-time director of the MIT Press. She then founded MIT's Visual Language Workshop (VLW) in 1975, which moved to the MIT Media Lab in 1985 as "one of its founding sources." As we will see, the Media Lab went on to be more important to the evolution of generative art than any other singular institution.

A visionary who saw the need to reinvent design in the face of a shifting world, Cooper believed:

The shift from a mechanical to an information society demands new communication processes, new visual and verbal languages, and new relationships of education, practice, and production.

John Maeda and the MIT Media Lab

AI Infinity - John Maeda, 1994

Many people may know John Maeda as the former president of the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) or as the author of the book The Laws of Simplicity. They may not know that Maeda started as an engineering student at MIT where he was fascinated by the work of Murial Cooper and the VLW. After completing both his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in engineering at MIT, Maeda earned a Ph.D. in design at Tsukuba University's School of Art and Design in Japan.

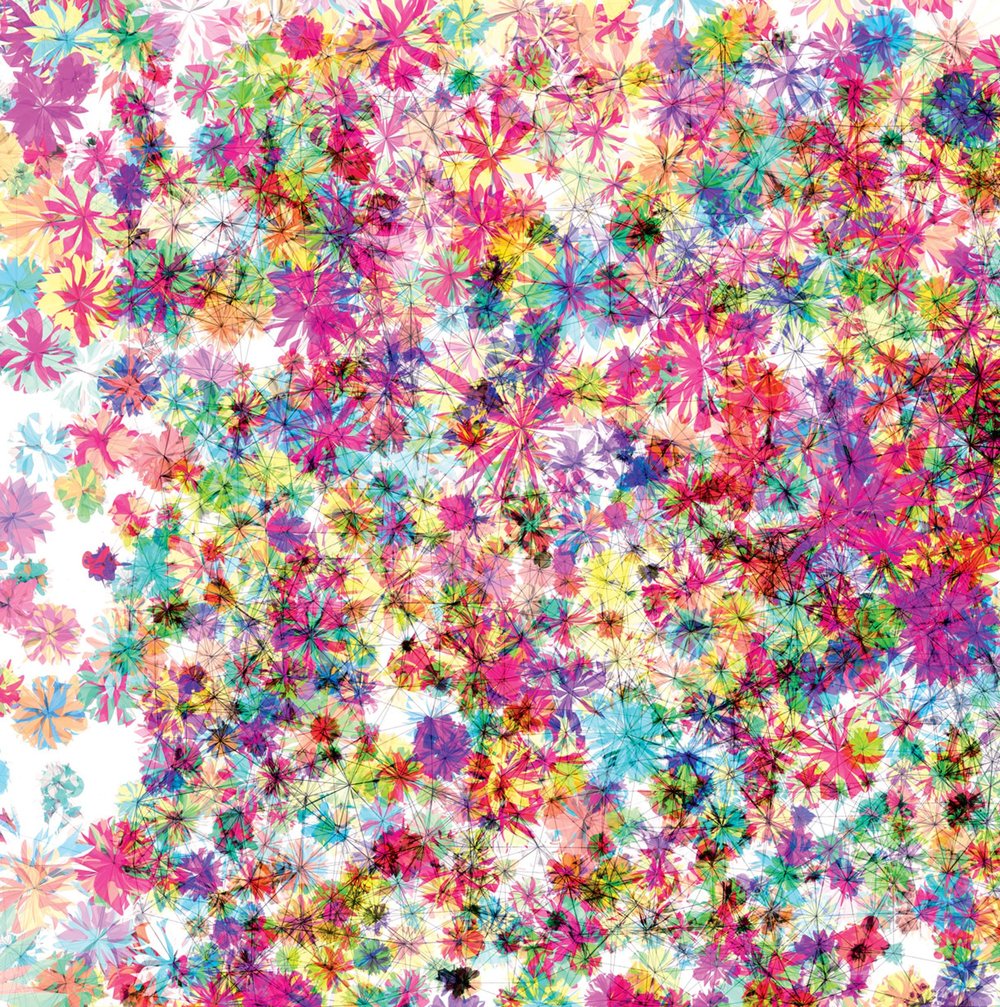

Florada - John Maeda, 1990s

Maeda returned to MIT and created the Aesthetics and Computation Group (ACG) within the Media Lab. As a group, ACG were heavily influenced by the prior work done by Murial Cooper's VLW group. Though Maeda is an accomplished generative artist with works in major museums, his greatest contribution to generative art was his invention of a platform for artists and designers to explore programing called "Design By Numbers."

In the late '90s Maeda recruited several brilliant and like-minded artists/technologists into the Media Lab to help work on “Design by Numbers,” including Ben Fry and Casey Reas. Fry and Reas took Maeda's “Design by Numbers” into classrooms around the world and eventually built their own free platform that could be shared outside of universities and used by anyone with an interest learning to sketch with code. They called this platform “Processing.”

Ben Fry, Casey Reas & The Birth of Processing

Processing made generative art accessible to anyone in the world with a computer. You no longer needed expensive hardware, and more importantly, you did not need to be a computer scientist to program sketches and create art. The language, the environment, and the community were all carefully crafted from the beginning make Processing accessible to as broad an audience as possible.

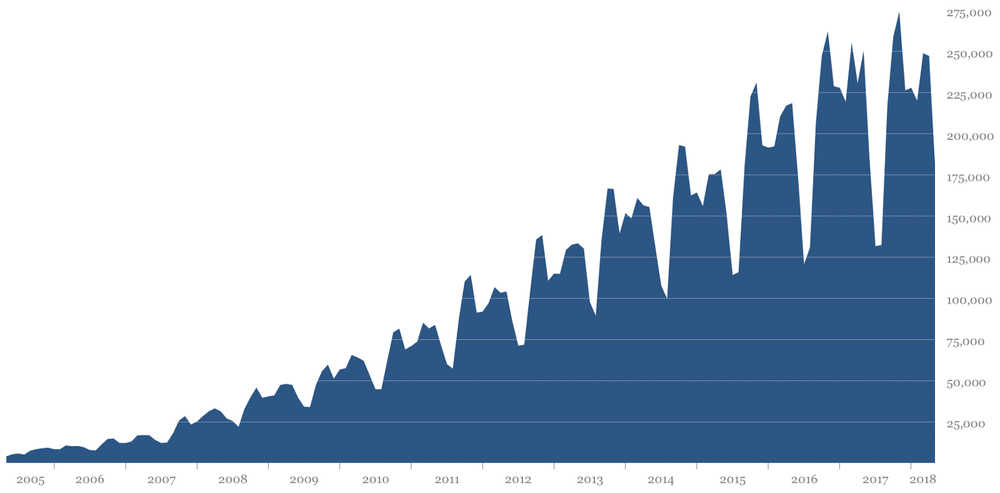

Processing is the key turning point in the production and proliferation of generative art. The massive growth is clear in the graph below.

Number of times the Processing software is opened on unique computers each month from 2005 to early 2018. This graph was originally published in Fry and Reas' excellent article on the history of Processing, "A Modern Prometheus." The peaks and valleys are correlated with the academic year with the highest points in the fall and the lowest during the summer. This data doesn’t account for shared computer use or when people turn this reporting off in the software preferences.

Fry and Reas have worked on Processing over the last 17 years, and and it has long been the preferred platform for the best known generative artists. In 2012 they created the Processing Foundation to “expand our reach and to support the software development,” and have added Daniel Shiffman and Lauren McCarthy as members of the foundation board. They have written an excellent post that details the evolution of the history of Processing that I highly recommend you read. Processing’s impact on an entire generation of artists and programers is nearly impossible to overstate - revolutionizing data visualization, pop culture, and fine generative art.

All Streets - Ben Fry, 2006

As an artist trained in traditional painting and drawing, I was a slow convert to appreciating digital art. I was reluctantly working with computers to make a living in the early 2000s, and it was my personal opinion for a long time that generative art was too hard-edged, lacked nuance, and was generally inferior to analog art. Then around 2006, I discovered Processing and the work of Jared Tarbell, and everything changed.

Jared Tarbell was creating what I still consider to be the most cutting edge, aesthetically pleasing, and engaging generative art way back in 2003 using a relatively early version of Processing. Tarbell, who went on to co-found the wildly popular handmade goods site Etsy, studied computer science at New Mexico State University. He describes himself as “one part Magical Mystery Tour (Lennon/McCartney), one part Brandenburg Concerto (J.S. Bach), and one part Somnium (Robert Rich)”.

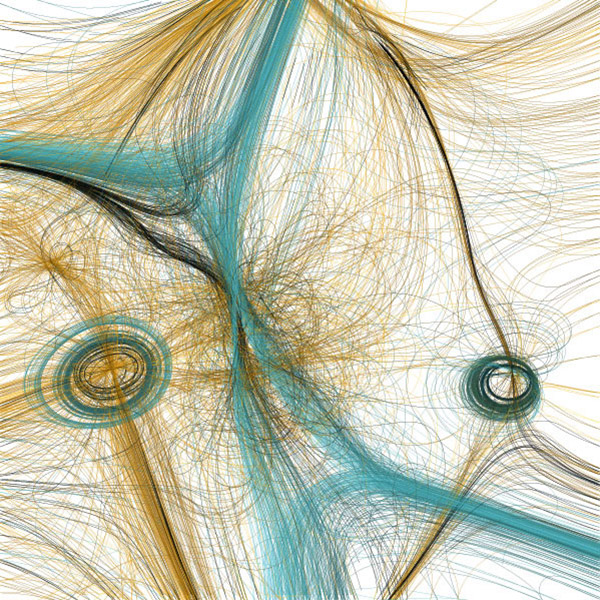

Substrate - Jared Tarbell, 2003

For me, Tarbell's work is the perfect generative art. It is the poster child for the duality of chaos and control, and has an intense level of visual complexity that slowly emerges from simplicity, making it feel more like it grew out of the soil than coming from algorithms.

Intersection Aggregate - Jared Tarbell, 2004

Tarbell's code-driven artworks have a pulse. He makes the digital feel as organic as any analog art I know of, but it is created through code and is comprised of pixels. His work was a step change for me in terms of believing computers can produce art at the highest level.

Bubble Chamber - Jared Tarbell, 2003

Tarbell's explanation of his process reinforces the concepts of controlled randomness in generative art that we have been discussing.

When you write a program, it’s going to be executed the same way every single time. So if you define a system like this where things can happen at random, as the creator, you can be surprised by your own program, which is really great.

Before Processing, Tarbell was part of a group of generative artists developing work on the Flash platform from Macromedia (now owned by Adobe). His site Levitated.net served as an educational resource for a generation of artists seeking to better understand how to code in Flash. You can still access his open source code on the site.

Joshua Davis, Flash, and Praystation

One of the artists Jared Tarbell cites as a major influence on his work is Joshua Davis. Since 1995 Davis has been using programming to produce art. He is among the first and best known artists to use Flash to create generative art.

You likely remember Flash. We all had a plugin for it in the early 2000s that added animation and interaction to the web. Though Davis attended Pratt first for painting and then for design, his style is largely self-taught. He emerged from a life of hard partying to lead a movement of Flash artists through a "shit-load of hard work" and continues to create impressive work. As he describes it:

Around 1998 I bought my first domain, called praystation.com. I was stoked! I slowly progressed and became more aware of design; I sort of realized who I was and what I was doing, without even knowing I was doing it. There was just a moment when I thought, “I’m a computer artist now! When did that happen?” I had finally found the new form of expression I had been looking for: I was going to use technology to make art.

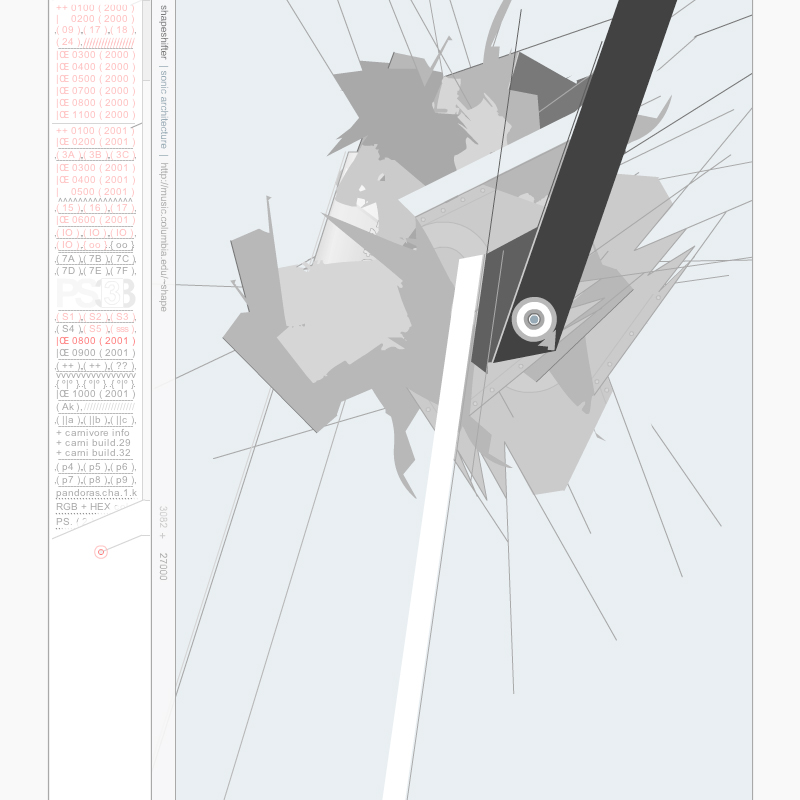

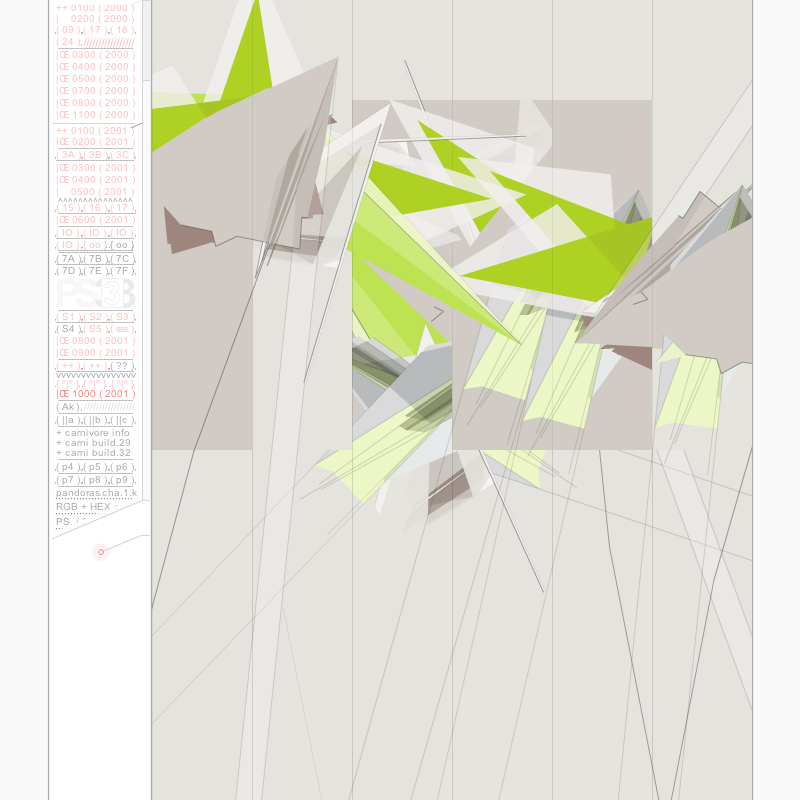

ps3-praystation-v1 - Joshua Davis, 2001

Shapeshifter|Sonic Architecture - Joshua Davis, 2001

ps3-praystation-v1 - Joshua Davis, 2001

Davis’ unusual blend of hard work and extreme generosity was critical in spreading Flash as a platform to other artists for generative art. He was one of the first generative artists to make it a point to share his code by going “open source” so others could learn from him.

I love giving stuff away. I like it because that’s just what DIY culture tells us. It’s about freedom of knowledge: I truly believe that, as humans, we have more to gain by sharing what we know than trying to profit and hoard it.

In 2001 Davis's "Praystation" won the Ars Prize Technica, and his work is now in the Cooper Hewitt museum.

Artificial Intelligence & Generative Art

AI Generated Landscape #6 - Robbie Barrat, 2018

Though you may notice that the fluid organic imagery is a departure from the geometric abstraction we have seen so far, AI art is a subgroup of generative art. Much of the new work in AI art is being created by GANs (generative adversarial networks). GANs are a concept based on neural networks that computer scientist Ian Goodfellow came up with back in 2014. If it sounds complicated, don’t worry, we’ll simplify it a bit.

First off, GANs are comprised of two neural networks, which are essentially programs designed to think like a human brain. In our case we can think of these neural networks as being like two people: first, a "generator," whom we will think of as an art forger, and second, as a "discriminator," whom we will think of as the art critic. Now imagine that we gave the art forger a book with 1,000 paintings by Picasso as training material that he could use to create a forgery to fool the critic. If the forger looked at only three or four of those Picasso paintings, he may not be very good at making a forgery, and the critic would likely figure it out pretty quickly. But after looking at enough of the material and trying over and over again, he may actually start producing paintings good enough to fool the critic, right?

This is precisely what happens with GANs in AI art. Artists like Robbie Barrat have been exploring the creative potential of these systems for image-making for several years.

Nude Portrait - Robbie Barrat, 2018

Barrat did an excellent job of explaining this process to me in more detail (and his role as the artist within it) during our interview back in April, 2018.

But what happens is there is this thing called latent space that emerges after you train the GAN. All the possible paintings that are possible are laid out in highly dimensional space you are feeding into the generator. But the way they are laid out isn't random, it truly makes sense. So if you want to get a similar painting to your previous painting, you can pick a point that's very close to the point for your first picture. But some of the dimensions actually mean things like color scheme. So if I had a generation that I wanted to make more colorful, I could adjust one of the dimensions. So I do have some control, but only after the fact. I can't tell the GAN to produce a specific painting, but if I find a painting I like, I can then make adjustments to it.

This may sound a bit technical, but it should be clear that artists have a great deal of control over the process - in fact, that is where the artistry comes in. I would encourage you to read my full interview with Robbie Barrat, as I feel he does a great job of explaining the foundational information needed to understand GANs as part of appreciating AI art.

For his latest project, Robbie gathered images from the Balenciaga online fashion catalog and used them to train his AI model. The GANs have been producing radical new fashions and styles unlike anything a traditionally trained human fashion designer would ever come up with. Barrat particularly likes the absence of symmetry, the random placement of pockets, and the addition of non-functional adornments like handheld tassels.

AI Fashion - Robbie Barrat, 2018

AI Fashion - Robbie Barrat, 2018

Barrat explained to me that he is using Pix2Pix technology in combination with DensePose to map the new AI outfits to the models. DensePose tries to estimate human poses and "...aims at mapping all human pixels of an RGB image to the 3D surface of the human body." A simpler explanation of this is that Robbie is training the AI to not only recognize the clothing in the Balenciaga catalog of clothing, but also the poses of the fashion models, and is then mapping the new fashions on to AI-generated fashion models and postures. Barrat explained:

pix2pix is the same thing as GANs, except instead of taking in noise, the generator takes in one picture and tries to output another that goes along with it, and then the discriminator looks at both pictures and its task is no longer figuring out if the images are generated or not, but rather if they make up a good pair.

Example showing use of DensePose and Pix2Pix

Based on the proliferation of news stories of late, there is no doubt that the use of AI in art is a topic of interst to the general public. A separate and maybe more important question is, "Is the art itself very interesting?" Robbie Barrat's art was the first to cross that bar for me. As AI art, it has that timeless quality found in much of the great art we find in our museums. A good test of high quality AI art is that you should be able to appreciate the end result even if you did not know it was created with AI (though the tools are fascinating, as well). Mario Klingemann is another artist who passes this test with flying colors.

Their styles are completely unique and distinct, but it does not surprise me that Barrat frequently credits Klingemann as inspiring his own techniques. Barrat recently said on Twitter:

I owe a lot of credit to @quasimondo for coming up with the DensePose + Pix2Pix method that I'm using for all this fashion stuff. Check out his work - he's got very compelling results from using this process with actual portraits as training data.

Barrat is spot on. Klingemann's recent Pix2Pix/DensePose works are aesthetically fresh and refined in a way that more hastily produced AI portraits that have been generated with AI are not. Klingemann's works are like revisionist art histories: they boil everything creepy about old paintings down into digital-surrealist masterpieces - you can almost smell the dust on the surface. They make me feel like I am a six year old on acid, lost in the “Art of the Americas” wing of the Boston MFA. Those scornful patriarchal, puritanical stares are made that much creepier by the melting abnormalities and deformations Klingemann introduces with his neural networks.

DensePose vs. Pix2Pix - Mario Klingemann, 2018

DensePose vs. Pix2Pix - Mario Klingemann, 2018

DensePose vs. Pix2Pix - Mario Klingemann, 2018

Klingemann knows his work is creepy, and that is how he (and I) like it. When the question of whether or not AI art is "attractive" recently came up on Twitter, Klingemann tellingly responded:

My goal is to make interesting images. Not sure if you know my work, but the average feedback is "nightmare fuel," "creepy," or "uncanny"... I personally prefer ugly over boring, conventional, normal, non-challenging or derivative.

To that I say amen. I engaged in the Twitter chat and asked Klingman his thoughts on who owns the artwork - the human or the machine - a question an art reporter friend of mine had asked me in an interview that morning. Klingemann responded:

Like with any other machine, the owner or the operator of the machine owns it. Ask any photographer or pianist.

I was not surprised by his reply, as it echoes that of so many other generative artists in this post who have had to answer the questions about what role, if any, they play in the work they create.

I am excited to see AI technology made more accessible to artists. Cristóbal Valenzuela has been designing tools that do just that, first, with his "Text 2 Image" tool that lets you type in words which the AI then tries to draw (with varying results). For example, I typed in "a man snorts bananas in a spaceship," pressed enter, and it produced the following image:

When you can produce an image or an effect with the push of a button, it usually gets old quick. So it is not hard to imagine that we will see something akin to the tsunami of images with Photoshop filters we were inundated with in the early ‘90s. In fact, Valenzuela is building a tool suite not unlike Photoshop, but leveraging AI to democratize the new tools for artists and designers. I'm not going to lie, I want to be first in line to play with it.

As AI technology becomes increasingly available, artistry and technical advancement will only become more important in separating the remarkable AI artists from those repurposing old tools built by others or simply pushing a button to achieve an overused visual paradigm. I remain fascinated by the space and will continue to watch artists like Robbie Barrat, Mario Klingeman, Tom White, Helena Sarin, Memo Atken, Gene Kogan, and others closely as their work evolves. I should also note at the time of this writing the traditional art world has started to take notice.

Summary and Conclusion

This post stems from me hearing too many people say they "do not like digital art.” Saying this is like saying "I do not like paintings," as digital art is so broad a field with generative art just being one part of it. I thought surely if people better understood the genre, they would have a better appreciation for the skill of the artists and the art they produce.

My goal was to help you fall in love with generative art - or at least give you a better understanding of it - without having to talk about code and math. Your appreciation of this genre will only improve if you explore the algorithms and programming behind the work. But same as you do not need to know how to paint to appreciate paintings, I believe you can appreciate generative art without understanding programming.

Though it became quite lengthy, this post was also not intended as a comprehensive history of generative art. Many amazing artists and key practitioners were not included. This article is simply one path through the history of generative art that highlights many of the artists I admire. I'd be thrilled to write the full story if given a book advance (hint, hint).

In summary, let’s take a look back at what we have learned:

- Generative art is an extension of central themes from 20th Century art

- The artists play a major role in the outcome of the work

- The process is very similar to traditional artmaking

- Generative art has its own rich history going back to 1960

- Women have played and continue to play major roles in this genre

- MIT has been an incubator for brilliant generative artists

- In the last two decades the genre has exploded as a result of the open source movement, improved tools like Processing, and a supportive community

- AI art using GANs, Pix to Pix, and DensePose is a subgenre of generative art

- As with all generative art, AI art is largely driven by human guidance

I studied art history in undergrad and earned an MFA in digital media, so I feel I have some qualifications to write a blog post like this. But in many ways it is not my story to tell. There is a strong chance I have made mistakes, and if I have referenced your work here and have gotten anything wrong, please know that I included your work in this post out of great appreciation and respect for what you do. Feel free to email me any corrections at Jason@artnome.com.

Finally, some of you may have noticed that the feature image for this article is by artist Manolo (Manuel Gamboa Naon), but I did not mention him in the text. This was intentional, and his work is included as a teaser. Along with Jared Tarbell, Robbie Barrat, and Mario Klingemann, Manolo is one of my favorite generative artists. I was lucky enough to interview him a few months back for feature piece that is now available. I could not limit myself to just a few paragraphs and one or two of his works - I'm hope you enjoy the interview!